|

During a recent trip to the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, we discovered an educational and cultural emphasis on voice and silence as offering opportunities for contemplation.

The Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto, claimed that ‘Beauty is the harmony of purpose and form’. His influence is evident in the new Department of Education’s building at Jyväskylä, in which straight lines merge seamlessly with multiple curves to create spaces where students and staff may think both together and alone. The proportioned white modernist exterior has large windows that let what little light there is at this time of year into a large public atrium. Glass-fronted offices and seminar rooms are arranged around the edge of the atrium, but teaching and meetings spill out into the central area, where different configurations of space and seating allow for students and staff to work together while sitting, moving, standing, and kneeling around low tables. We also see a student lying across a table top during a seminar. When giving a presentation and engaging in discussion with colleagues in the atrium, we do so alongside a nearby circle of students participating in a group activity, others doing something with large poles (what or why, is unclear!), and a one-year-old child wandering together with an adult. The circular arrangement of our meeting area keeps our attention, but still we wonder why background activity and sounds never seem to provoke irritable requests to ‘Shhh’. Perhaps this has something to do with living in snow, which muffles distant sounds and attunes the senses to what is immediate. During our visit, we are delighted to glimpse a hare, silhouetted against the white landscape; it pauses, listening intently before crossing a wooded path. Our hosts tell us that Finns are also shy, as well as attentive and curious. They prefer to communicate efficiently without great elaboration, not wanting to stand out too much; they are also comfortable sitting together in silence. In an open society, where there are plenty of opportunities to talk and to be heard, it seems that silence is also highly valued as a form of contemplation and respectful togetherness. Silence is more than a technique to discipline bodies although, we are told, it is still possible to slip into conforming pedagogies and practices in these more democratic education spaces. (We have written about silence as discipline in English primary schools). On our last day in Helsinki, we visit the Kampin Kappeli (Chapel of Silence), a cylindrical building, constructed in 2012 out of spruce, ash and alder. Situated in a busy shopping area, it offers a place of interior calm, like the eye of a tornado. Here we experience what Deleuze describes as the ‘relief to have nothing to say, the right to say nothing, because only then is there a chance of framing a rare, and ever rarer, thing that might be worth saying’. We take up the opportunity to explore the inner self; making sense of the many ideas, thoughts and emotions experienced on our trip; and becoming open to other ways of being. When a large group of tourists enter noisily out of the rain, we tune out the irritation and into the way rustling waterproof coats and squelching footsteps flood the chapel like a slowly ascending wave. We wonder what cannot be spoken, and what it is not possible for us to hear, during our brief encounter with Finland. We hope to return before too long to collaborate further with our wonderful colleagues at the ‘OIVA’ Project, working on issues of equality and rights in Early Childhood Education and Care. Also, we wish to hear more about a silence that frames those things worth paying attention to. Above painting: ‘Silence’, by Helene Schjerfbeck, currently exhibited at the Ateneum Gallery, Helsinki.

0 Comments

We are delighted that the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) has provided us with a small grant through its Impact Acceleration Account. It means that we can extend the work we undertook with teachers and leaders in a workshop in the University of Sussex[1] out into the community and into schools to further interrogate ideas of uncertainty and conformity. This time, however, as suggested by teachers with whom we worked previously, the focus of our attention will be upon issues associated with climate change.

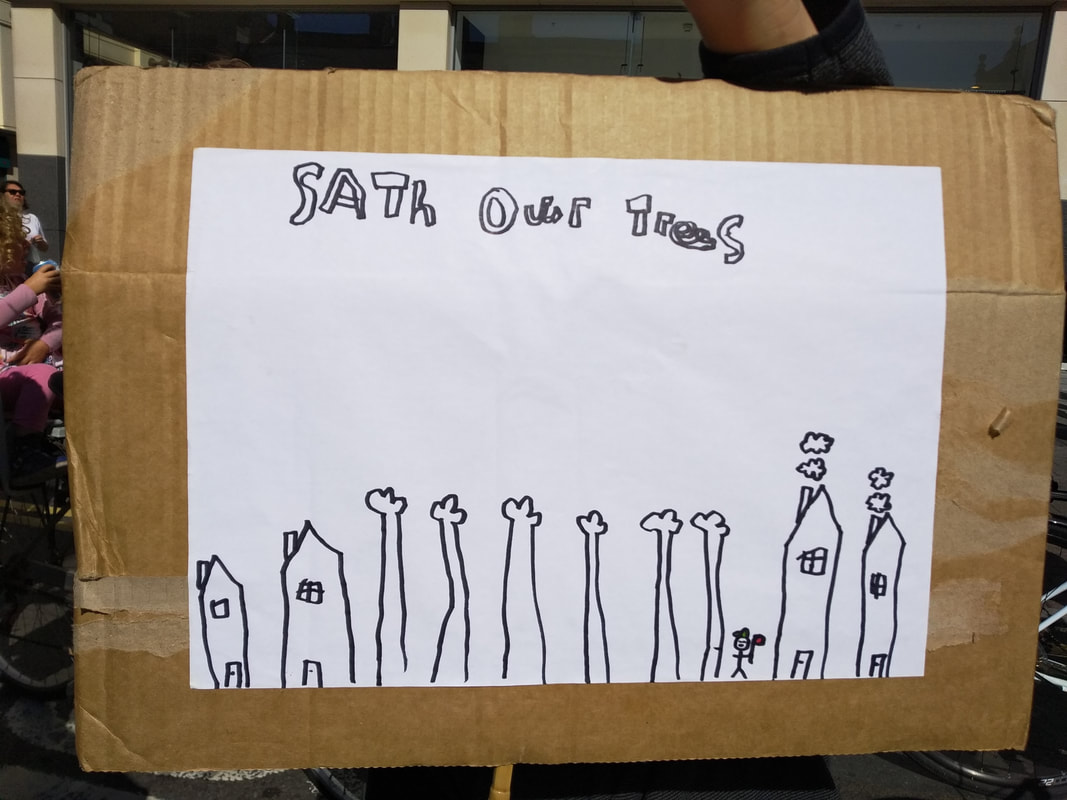

The small-scale project aims to create the educational conditions for teachers and children and young people to engage with, and act, in response to personal, local and global challenges of global heating, many of which are inherently uncertain, where ‘answers’ are often complex and unclear. This requires us all to acknowledge that what we might do – both within and beyond school - and what we feel, can be deeply unsettling and anxiety-inducing for young and old alike. We want to work with these disparate feelings and uncertainties in this project, so that pupils (with the support of staff) can explore their own relation to climate ‘facts’. In so doing, we aim to support conditions that allow for what Hodgson, Vlieghe and Zamojski[2] suggest in their manifesto (mentioned in the podcast) are possibilities of transformation through the creation of ‘a space of thought that happens anew’ (p.17). We recently made a podcast for a week of ‘climate change crisis’ action at one International University in Germany for teaching colleagues and students thinking together. It highlights aspects of the work we will be undertaking through our impact work, placing it within the wider context of ideas of conformity and uncertainty for transformation in education. [1] Funded through a Quick Boost Impact Award along with colleagues, Sean Higgins and Fawsia Haeri Mazanderani by the Dept. of Education in the University of Sussex during the summer of 2019. [2] Hodgson, Vlieghe and Zamojski have produced a wonderfully accessible slim volume entitled a ‘Manifesto for post-critical pedagogy’ which frames a way to be and to act now, and to have ‘hope in the present (p.18) |

AuthorPerpetua Kirby & Rebecca Webb Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed