|

Last week in Copenhagen, at an academic seminar organised by the Danish School of Education (DPU), Aarhus University, I find myself laughing, along with other participants, at a poster drawing of the ideal listening pupil. It is one that will be familiar to many working in English primary schools: the child sits upright, facing forward, eyes looking ahead, hands folded nearly in the lap, feet together facing forward. I saw a similar poster during my research in Year One classrooms, along with the teacher’s rallying call ‘Remember good sitting and listening means good learning’. During a maths lesson, I observe two girls leaning forward and towards each other, resting their forearms on the carpet as they write answers to questions on whiteboards placed on the floor, when suddenly the teacher calls out: ‘Roz and Yaz, you’re not at home, you should not be lying down’. The logic that children should be sitting rather than inclining extends beyond learning in any simple pedagogical sense. The implied superiority of the vertical includes the moral reprimand to become upright, alone, independent, and excludes other possibilities. Virginia Wolf, in A Room of One’s Own, warned against ‘the dominance of the letter ‘I’ and the aridity, which, like the giant beech tree, it casts within its shade. Nothing will grow there.’

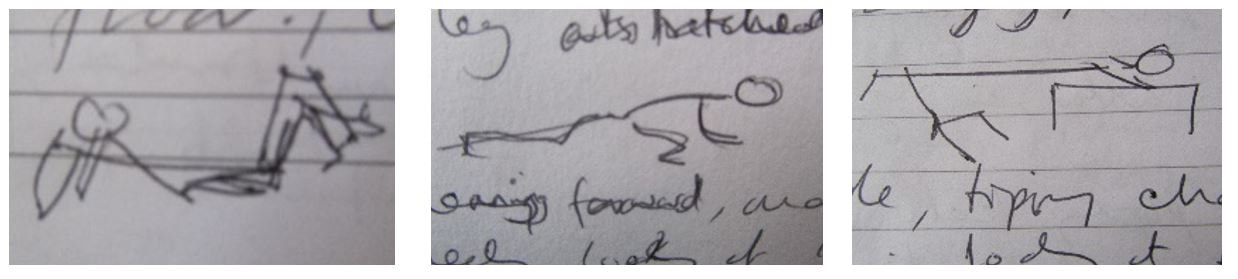

Sitting in the seminar, reminded of my own research, I begin to feel slightly uncomfortable laughing at the poster image, which sounds a critique of the representation of the ‘ready to learn’ child. I am alerted to the irony that we, the assembled seminar participants, are engaged in a similar pedagogy: sitting upright while listening attentively to Maggie Maclure’s fascinating presentation about early years literacy within a forest school setting. The irony is felt more acutely because the theme of the seminar is how to move away from critique as something negative - one that emphasises errors, according to pre-existing ideas of what is true - to one engaged in creative experimentation offering possibilities for change. Maclure acknowledges the on-going challenge for us researchers to adopt an affirmative critique given a long academic tradition of standing at a distance and casting judgement. This shift is something I grappled with during my doctorate. My supervisors commented that an early draft chapter showed a lack of redemption for the research schools. I felt shame, provoked by my display of ignorance, and the sense that I was an imposter in the academy. During a later writing retreat, I dipped into a copy of Moby Dick. There I discovered the Catskill eagle, ‘that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces’. This is a metaphor for those who can rise and profit from moments of suffering, rather than avoiding them as most of us so frequently do, ‘even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar’(ibid.). Even shame, in all its misery, can be productive (see Elizabeth Probyn). My partner’s family are from South Africa, where ‘Shame!’ is colloquially used to imply ‘cuteness’ and to demonstrate sympathy, as in ‘you poor thing’, but overused it whitewashes feeling. My shame became a wrenching out of myself; it demands a more ethical sensibility, alerting me to difficult feelings about my own and my children’s education, evident when I stand and write knowingly at a distance, rather than inclining, sensing and revealing my proximity to the school research participants. This includes recognising how I am entangled in the education system that I am attempting to critique. To shift my understanding of the classroom means not having the answers in advance; it means engaging in the sort of listening that Les Back described as recognising ‘the importance of doubts’ more than certainties. At the seminar, Dorthe Staunæs talked of another ugly feeling, envy, as the ‘shadow side’ of the use of data in education, including performance data. She beautifully illustrated with her own academic data – including graphs comparing numbers of academic publications – that invokes a desire of others and a fear of being left behind, while at the same time it motivates. The critique is felt in the intense envious ache of the belly, rather than imposed from outside. Staunæs suggested the need for careful curiosity in exploring the use of performance data, opening the possibility for doing things differently, rather than simply debunking its use. Children’s critique of the demand to learn mostly while sitting upright and still is felt in their aching and longing bodies. In my research, they repeatedly tell me they do not like sitting quietly and still for long periods on the hard floor: listening to things they do not understand or else already know. Their young bodies frequently cannot help but move and mingle with the human and inanimate, even when expected to sit still. Children look around, stretch arms and legs, twiddle fingers, rub limbs, pick scabs and noses, hold hands and move up close, braid hair and fiddle with clothing, run a hand along the smooth box of books or stroke the soft lion at the edge of the carpet, repeatedly replace a sticker, jiggle a leg or bounce a hair band. Bodies occasionally find a way to squat, kneel, lie down or even stand when expected to be seated. My field notebook sketches (see above) show Julia lying down during phonics, lunging on the carpet while the teacher explains an activity, and balancing her legs on the back of a chair during a table activity. In these moments of movement, children are looking after themselves, wrestling with their bodies, generally careful not to disturb the class or attract the attention of the teacher, demanding a ‘wisdom’ that Janusz Korczak observed in a 1930s Polish classroom. In her presentation, Maclure did not aim to challenge the dominant teaching of reading and phonics, which she suggests has a place in today’s classrooms. Instead, she explores how literacy in an outdoor tipi allows for a different kind of multisensory event, including sounds and bodies, offering something different to that achieved when sitting quietly in the classroom, where sounds are muffled and bodies stilled, aimed at ensuring children concentrate on listening for meaning. There is a value in learning to sit quietly – it is helpful, for example, when grappling with the complex theoretical and empirical ideas discussed during an academic research seminar – but what is needed, and what Maclure offers, are additional images of readiness for being taught, and an understanding of what each may offer and deny. Despite having made steps towards a more affirmative critique, I retain an uneasy sense of voyeurism at commenting on others’ education practices. There remains a space for a more detached critical voice, but more a need for researchers to work together with others involved in education. Staunæs runs workshops with teachers on how ‘data do more than they show,’ to identify ways to take care of teachers and students when using data. Maclure writes with early years practitioners to explore the possibilities of co-construction. The forthcoming TRANSFORM-iN EDUCATION launch event, on 10th December, aims to open up a space for conversations between educators, researchers, parents and others on how to foster the conditions to achieve the balance of conformity and transformation in education. We hope you will join us, in person or via live stream. There will be moments to sit and listen as well as to move and talk.

0 Comments

|

AuthorPerpetua Kirby & Rebecca Webb Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed