|

by Rebecca Webb, Emma Bernagozzi and Perpetua Kirby

What might uncertainty teach me? There is a growing recognition of the importance of teaching students about sustainability issues. But given the many uncertainties and unknowns, what kinds of learning approaches are appropriate?

0 Comments

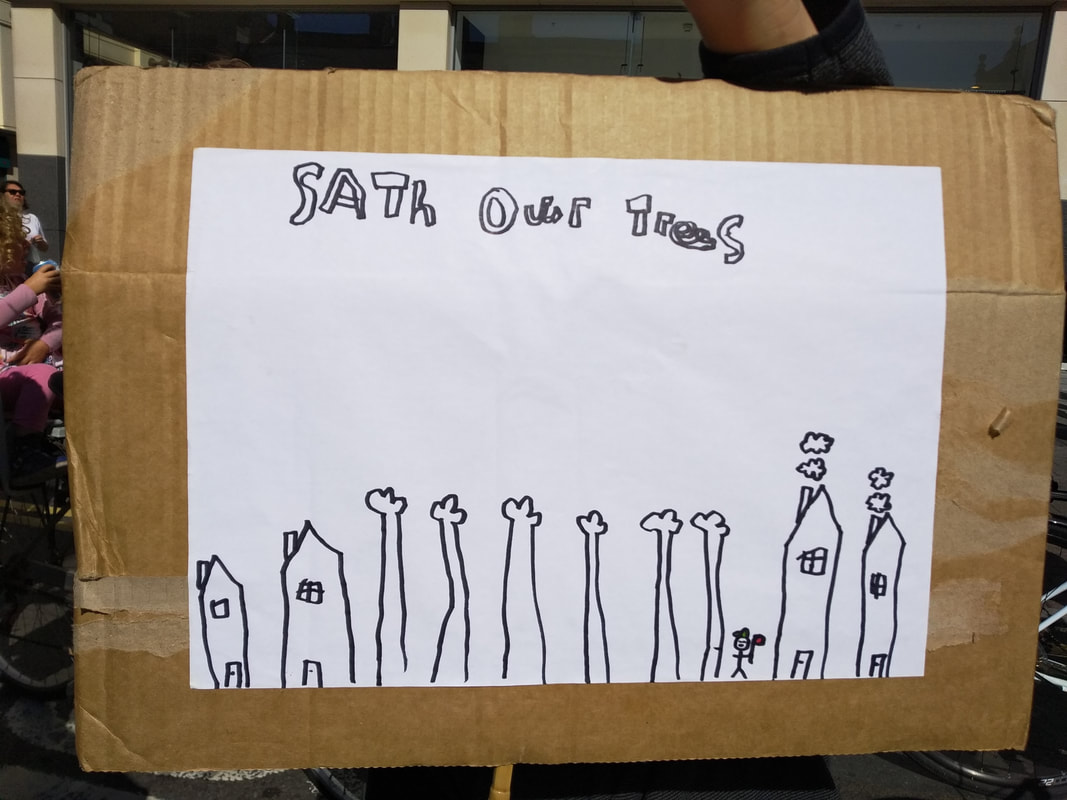

Radical action from the streets to the classroom: Climate youth protests have highlighted the radical space of the streets. As many students cannot participate in such action, we ask what a radical space of schooling might look like in response to the climate crisis.

Creating with Uncertainty: experimenting with creative methods for climate education with primary, secondary and special schools, together with sustainability experts at the University of Sussex.

IMAGE: Young people listen to a world never-before encountered inside a tree with soundscape ecologist, Dr Alice Eldridge. Image taken by Tunde Alabi-Hundeyin. How to tackle climate uncertainty without the anxiety: engaging with the uncertainty of climate using creative and discussion-based activities. (November 2021)

This article was first printed in the Financial Times on 8th March , 2021, and has been reproduced with their kind permission.

In a recent radio interview about the pandemic, a distinguished professor was asked whether we need to learn to live with uncertainty. Her response was that “uncertainty is the enemy of wellbeing”. Yet the situation is more complex than that, especially for the young who have actively engaged with uncertainty in their lives under Covid-19. Coronavirus has cast a shadow of doubt over many certainties. To realise that parents, teachers and even governments do not know what may happen can be destabilising. Yet research suggests that being open to uncertainty is important for wellbeing. It supports curiosity, deep thinking and hope. It should be central to children’s education. My colleague, Dr Rebecca Webb, and I set out to find how uncertainty is affecting young people. We examined the diaries of more than 50 people aged six to 20 across England, written during the first lockdown last May. What was striking is the extent to which young people grapple with unknowns. Their entries explore existential questions and the implications of government directives. They express fears, anger and confusion, plus the possibilities and joys offered by living under lockdown. They reimagine futures and engage humorously. One wrote: “We must all ‘Stay Alert’. Alert for what, someone walking round with a sign reading ‘I’ve got Covid-19’?” Schooling emphasises certainty, with subjects mapped and measured, as defined by national curricula. On the surface, this seems to work. The teacher is certain what they must teach. The students are certain what they must learn. There are right and wrong answers. Those giving correct answers receive good grades and go off full of expectation into the world. Yet the world they enter is filled with uncertainty. “We were never taught what uncertainty feels like,” one student told us. “Things were always planned out for us and we were always working towards something certain. The bubble of certainty begins to crack as we are on the edge of being poured into real life.” In schools, young people face tough Covid-19 compliance rules but, on leaving the gates, they navigate many decisions without clear answers. This might include what to do if friends refuse to social distance or if families are vaccination sceptics. Students need opportunities to work out how to respond to their feelings, external pressures and competing information. Most are conscious of uncertainty even if they struggle to articulate it. A mother told us that 10 months into the pandemic, she realised her 13-year-old daughter’s anxiety, when she said, “I really want you to get the vaccine, because then I can relax”. Our education system will never succeed in shielding everyone from uncertainty. Nor should it try. This simply leaves young people to worry before, perhaps, telling an adult. Working through uncertainty with support is what builds resilience. Facing uncertainty alone rarely does. A few schools embrace uncertainty. For example, the International Baccalaureate, delivered in some sixth forms, supports students to “approach uncertainty with forethought and determination”. Doing so can enable students to work with complexity and to live respectfully with others. After all, uncertainty is integral to most decisions in business, finance, politics and personal lives. This makes dealing with uncertainty an educational imperative. Rather than being the enemy of wellbeing, uncertainty offers an opportunity to build inner strength. This is a challenge for us all. But for young people in the maelstrom of peer pressure, testing, puberty and other challenges, it is far harder. Perpetua Kirby and Rebecca Webb both contributed to this article. What do you save from your home when the cyclone comes and waters rise? How do you respond when, out of necessity, your parents work for a logging company that threatens global warming and the last remaining Brown-headed Spider monkeys on earth? These are the types of uncertainties faced by young people living in the Sundarbans delta of northeast India, and the lowland Chocó in the north of Ecuador. In a new research study, we are working with partners in these two regions, with Dr Anindita Saha and Dr Citlalli Morellos (Tesoro Escondido Reserve), to support young people to reflect deeply on how they experience and connect to their local sustainability issues.

In each region, researchers and artists are working with young people aged between 12 and 20 years old. Using creative and interactive activities — such as drawing, mapping and film-making — young people are encouraged to engage with a complex range of thoughts, feelings and opinions that they might have. They can explore their experiences of sustainability through a range of different lenses, by:

The young people will be able to create artworks for themselves that suggest how they make sense of sustainability issues. They will exhibit their art locally. Those in the community will be invited to come along and look at, and talk about, the artworks with the young people who have produced them. There will be plenty of opportunities for discussion and deliberation. The purpose of this will be for everyone to consider any actions they may wish to take to address sustainability issues. The interdisciplinary research team working on this project is trying to mirror the creative, deliberative approaches of the young people. This means that they are required to bring their different disciplinary knowledge together. Researchers from education, life sciences, environmental history and the arts will work, learn and challenge one another over the next few months in new and unfamiliar ways.* Entitled Hope in the Present, the aim of the research is to find out whether using creative and deliberative approaches might shift young people’s sense of hope: through attending to what is worth preserving in their everyday lives and by identifying possibilities for taking action with others. * The research team includes those at the University of Sussex: Dr Rebecca Webb and Dr Perpetua Kirby (Education and Social Work), Dr Mika Peck (Life Sciences), Prof. Vinita Damodaran (Environmental History), Zuky Serper (artist), Tiffany Yan Wong and Juno Zhou (Childhood and Youth, Masters students). The Indian team: Dr Anindita Saha (museum and curation studies), Biswajit Mahakur (educationist) and Khitish Bishal (artist). The Ecuador team: Dr Citlalli Morelos (life sciences), Paola Ponciano (educationist) and Kata Kárath (filmmaker). Advisers: Prof. Janet Boddy (Education and Social Work, University of Sussex); Prof. Ian Scoones (Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex), Prof. Paul Basu (anthropologiest; curator; film-maker; School of Oriental and African Studies, London). The research is being funded by International Development Challenge Fund (IDCF) & Sussex Sustainability Research Programme (SSRP), financed by the University's Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) allocation. The title, ‘hope in the present’, is borrowed from Naomi Hodgson, Joris Vlieghe and Piotr Zamojski’s Manifesto for a Post-Critical Pedagogy. This time last year, in the autumn of 2019, some children and young people were opting to be out of school, on the streets, making a noise and voicing their concerns for climate action. Contrast this autumn: children and young people are back in school following on from the first Covid-19 ‘lockdown’. And they are very quiet.

There has been an understandable, and pressing, national imperative to ensure children are in school to accrue the socialisation and learning benefits this offers them. But there appears to be a renewed unquestioned emphasis on conforming and regulatory practices that mask what students have to say and need to communicate. As pupils, they are back sitting in rows in class; facing the front; listening to what the teacher has to impart; mindful of strictures about what behaviours are considered acceptable, cognisant of sanctions and punishments if these are flouted. While such measures may help to protect students from the Covid-19 virus, there is the danger that they also shield them from engaging with pressing complexities and uncertainties in their immediate lives and beyond. Such matters include living with Covid-19 and its attendant everyday hardships for many families; the issues of race inequity thrown up by campaigns highlighting Black Lives Matter; and the ongoing global crisis of sustainable biodiversity and of climate change. Yuval Noah Harari (author of Sapiens and Home Deus) raises concerns about the normalisation of surveillance within society, including within the institution of the school, during Covid-19, describing this moment as a ‘major test of citizenship’. In schools, surveillance technologies and practices long pre-date the current pandemic however. A teacher explained to us that children are taught that ‘it’s never okay to say No to an adult’, for example. Student movement is so tightly monitored in school (including technologies such as CCTV), that the academic, Andrew Hope, warned of an increasing surveillance acceptance and tolerance, with schools increasingly becoming laboratories for ‘surveillance futures’. Schooling only for conformity is never sufficient within a system with democratic ideals. Gert Biesta, the educational philosopher, illustrates this using the example of Rosa Parks and Adolf Eichman. Both learned to attend to and to listen well to the expectations of their day encoded within public institutional practices. Each made very different choices, however. Parks knew that it was considered unacceptable for people of colour to choose where to sit on a public bus, but still she rejected the bus driver’s order when told where to sit. Eichman, the Nazi SS commander responsible for managing the mass deportation of Jews to extermination camps, claimed in his defence that he was doing as he was told. From a humane and existential perspective, being socialised into learning only ever to conform requires constant scrutiny and challenge. There are many internal and external influences on why humans might act as they do, but a key focus for educators, says Biesta, is to encourage the ‘I’ to be able to step forward and to be out of line. Rosa Parks’s ‘I’ stepped forward, enabling her to say ‘No’, whereas Eichmann withdrew his ‘I’, claiming ‘It wasn’t me, I just followed orders’. One test of democratic citizenship for schools is whether there exists the agreed and accepted opportunity for pupils to say ‘No’ and to act otherwise. This is not about the granting of a freedom to do simply whatever they might want, but about the opportunity to make decisions about how to be, rather than yielding to many internal and external forces and routinised expectations. The role for education and educators is to remind students of their citizenship and to support them in finding out how they might exist in the world, alongside other humans and in balance with animals and plants. This requires opportunities to examine, discuss, question, feel and deliberate difficult questions which assume ongoing exploration and contestation, where the teacher should not be placed in a position of feeling she must have an answer, and the ‘right’ one at that. In the same way that biodiversity allows for the resilience of individual plant species to thrive, a diversity of experiences and perspectives is important for any human community to buffer itself from threats and to reorganise itself in response to the uncertainties of change. During the Second World War, the citizens of Denmark were unique amongst all European countries for openly speaking out against Nazism. For those Germans living in Denmark, the exposure to mass local resistance resulted in them sabotaging central orders, and acting otherwise, helping to ensure the large majority of resident Jews in Denmark survived the war (See the work of Hanna Arendt for a detail description of this). Today’s complex and challenging issues for children and young people, whether in school, at home or out and about in their wider worlds, involve them, with others, in making difficult decisions in relation to the current pandemic, Black Lives Matter and the climatic threat to the planet. Many young people feel that taking on the viewpoints of others and always doing what is expected will be insufficient when future generations asks: ‘. . . what did you do?’ They are exploring other ways to exist in the world, but often alone without the support of adults. Schools are the public institution that can and should provide that support as imperative of a democracy: ‘[My parents] think that me getting this day of education will be more important than making a stand against the systematic oppression that is happening… I think it’s really important to do this because if we are successful and, say, however many years in the future I have all these amazing stories to tell my grandchildren about what I did to help.’ (Mickey, school climate striker, age 17; cited in research by Benjamin Bowman) In a recent blog for Sussex Bylines, we expand on some of the issues explored here: Let the children speak What does this moment of uncertainty of COVID-19 signal for the future of education? The intensity and scale of the current pandemic signals the need to look at how children and young people experience uncertainties in their diverse lives. COVID-19 is the most recent of many pressing challenges. Climate change being another notable example. The current Black Lives Matter protests are also a powerful reminder that uncertainties are experienced unequally and are more acute for those living with economic precarity, vulnerabilities and discrimination. There are currently many public health messages on keeping safe and well, such as washing hands, but research by Lucy Bray and colleagues shows that it is insufficient simply to tell children to follow advice, without also exploring their difficult questions. Children and young people need opportunities for critical engagement with scientific knowledge to make sense of it in relation to their own lives — washing hands, for example, is not easy for the 2 million Americans without running water. Children, like adults, are becoming more versed in epidemiology modelling — including R values, herd immunity, and flattening curves — emphasising the need to support them to understand and tolerate that “uncertainty is the engine of science” (Prof Tom Jefferson, epidemiologist). There are now live opportunities to discuss competing and diverse disciplinary knowledge (see Louise Ryan’s blog), with the understanding that science knowledge is negotiated not fixed (see John Dupré's blog), and can be used for political ends. By deliberating different sources of knowledge and ideas, and sharing experiences, they can participate in current debates, including how to emerge from lockdown and return to school in ways that feel safe. We are currently working with a group of teachers, and Caroline Hickman (Climate Psychology Alliance) — whose work focuses on children’s emotional responses to the climate and biodiversity emergency — to explore parallels between the uncertainties (including anxieties) of climate change and COVID-19. Schools are concerned about both. We plan to open-up spaces for teachers and children to explore what it means to return to school in a context where they must adapt to an on-going shifting pandemic (and post-pandemic) context. This includes taking a moment to reflect on what we might want to continue prioritising from before lockdown, and the possibilities to create learning environments that engage children with change and unknowns, in ways that acknowledge their experiences, feelings and thoughts. We shall be using outdoor settings to ensure physical distancing, but also as a conduit for reflection, healing, and an appreciation of how our lives our interconnected, including with the natural world. The children’s author, Michael Rosen, reminds us that when faced with the perils and possibilities of adventure, ‘We can’t go over it. We can’t go under it. Oh no! We’ve got to go through it’, and that this is best done together. For children, this includes the helping hand of a trusted adult. Such supportive conditions are key to building the types of community resilience that allow for something new and exciting (if a little scary) to emerge. Acknowledging existing uncertainties, rather than ‘trying to find a way to kill uncertainty’, suggests Riel Miller from UNESCO (see BBC Radio 4’s Start the Week), is a way to appreciate novelty, diversity and difference. It offers the possibility to cultivate the confidence and imagination to explore ways to express these values in ‘radically different ways.’ Acknowledging uncertainty requires paying attention to children as they puzzle over difficult questions, those where adults — including teachers, parents, scientists and politicians — do not know the answers in advance or where things might lead. Such opportunities aim to cultivate children’s capabilities and hope to tolerate and respond to uncertainties, rather than being put-off by complexity, anxiety or futility. Wim Lambrechts and James Hindson list a range of ‘uncertainty capabilities’ under the following headings:

In education, we take children’s futures seriously, through defining the knowledge and behaviours that might enable them to lead ‘successful’ adult lives. Engaging with existing knowledge and being socialised to ‘fit in’ is important, but so too is working with the uncertainty of what is currently known or possible to do and be, and what might follow. Working with uncertainty requires adults to let go, if only for a moment, of assumptions about what will or can happen, what children know or need to know, and how children live their lives (now and in the future). Working with uncertainty requires us to pay attention to how children themselves make sense of their diverse worlds: encouraging them to draw on their experiences and what is already known, as well as to look ahead to the kinds of worlds they’d like to create. This informs how they might live well now, together with others. This engagement with uncertain futures, suggests UNESCO, offers the necessary ‘futures literacy’ skills essential for responding to the 21st century challenges. Including pandemics. And climate change. And social injustices. During a recent trip to the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, we discovered an educational and cultural emphasis on voice and silence as offering opportunities for contemplation.

The Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto, claimed that ‘Beauty is the harmony of purpose and form’. His influence is evident in the new Department of Education’s building at Jyväskylä, in which straight lines merge seamlessly with multiple curves to create spaces where students and staff may think both together and alone. The proportioned white modernist exterior has large windows that let what little light there is at this time of year into a large public atrium. Glass-fronted offices and seminar rooms are arranged around the edge of the atrium, but teaching and meetings spill out into the central area, where different configurations of space and seating allow for students and staff to work together while sitting, moving, standing, and kneeling around low tables. We also see a student lying across a table top during a seminar. When giving a presentation and engaging in discussion with colleagues in the atrium, we do so alongside a nearby circle of students participating in a group activity, others doing something with large poles (what or why, is unclear!), and a one-year-old child wandering together with an adult. The circular arrangement of our meeting area keeps our attention, but still we wonder why background activity and sounds never seem to provoke irritable requests to ‘Shhh’. Perhaps this has something to do with living in snow, which muffles distant sounds and attunes the senses to what is immediate. During our visit, we are delighted to glimpse a hare, silhouetted against the white landscape; it pauses, listening intently before crossing a wooded path. Our hosts tell us that Finns are also shy, as well as attentive and curious. They prefer to communicate efficiently without great elaboration, not wanting to stand out too much; they are also comfortable sitting together in silence. In an open society, where there are plenty of opportunities to talk and to be heard, it seems that silence is also highly valued as a form of contemplation and respectful togetherness. Silence is more than a technique to discipline bodies although, we are told, it is still possible to slip into conforming pedagogies and practices in these more democratic education spaces. (We have written about silence as discipline in English primary schools). On our last day in Helsinki, we visit the Kampin Kappeli (Chapel of Silence), a cylindrical building, constructed in 2012 out of spruce, ash and alder. Situated in a busy shopping area, it offers a place of interior calm, like the eye of a tornado. Here we experience what Deleuze describes as the ‘relief to have nothing to say, the right to say nothing, because only then is there a chance of framing a rare, and ever rarer, thing that might be worth saying’. We take up the opportunity to explore the inner self; making sense of the many ideas, thoughts and emotions experienced on our trip; and becoming open to other ways of being. When a large group of tourists enter noisily out of the rain, we tune out the irritation and into the way rustling waterproof coats and squelching footsteps flood the chapel like a slowly ascending wave. We wonder what cannot be spoken, and what it is not possible for us to hear, during our brief encounter with Finland. We hope to return before too long to collaborate further with our wonderful colleagues at the ‘OIVA’ Project, working on issues of equality and rights in Early Childhood Education and Care. Also, we wish to hear more about a silence that frames those things worth paying attention to. Above painting: ‘Silence’, by Helene Schjerfbeck, currently exhibited at the Ateneum Gallery, Helsinki. We are delighted that the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) has provided us with a small grant through its Impact Acceleration Account. It means that we can extend the work we undertook with teachers and leaders in a workshop in the University of Sussex[1] out into the community and into schools to further interrogate ideas of uncertainty and conformity. This time, however, as suggested by teachers with whom we worked previously, the focus of our attention will be upon issues associated with climate change.

The small-scale project aims to create the educational conditions for teachers and children and young people to engage with, and act, in response to personal, local and global challenges of global heating, many of which are inherently uncertain, where ‘answers’ are often complex and unclear. This requires us all to acknowledge that what we might do – both within and beyond school - and what we feel, can be deeply unsettling and anxiety-inducing for young and old alike. We want to work with these disparate feelings and uncertainties in this project, so that pupils (with the support of staff) can explore their own relation to climate ‘facts’. In so doing, we aim to support conditions that allow for what Hodgson, Vlieghe and Zamojski[2] suggest in their manifesto (mentioned in the podcast) are possibilities of transformation through the creation of ‘a space of thought that happens anew’ (p.17). We recently made a podcast for a week of ‘climate change crisis’ action at one International University in Germany for teaching colleagues and students thinking together. It highlights aspects of the work we will be undertaking through our impact work, placing it within the wider context of ideas of conformity and uncertainty for transformation in education. [1] Funded through a Quick Boost Impact Award along with colleagues, Sean Higgins and Fawsia Haeri Mazanderani by the Dept. of Education in the University of Sussex during the summer of 2019. [2] Hodgson, Vlieghe and Zamojski have produced a wonderfully accessible slim volume entitled a ‘Manifesto for post-critical pedagogy’ which frames a way to be and to act now, and to have ‘hope in the present (p.18) |

AuthorPerpetua Kirby & Rebecca Webb Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed